It’s hard to make decisions about composite materials and manufacturing methods because of the huge number of variables at play for almost every choice. Every where you look – decisions! And it’s almost never obvious what making one will do to the range of possibilities for all the others. This is one of the biggest obstacles to applying composite materials to new types of manufacturing problems.

I have come to the conclusion that a few questions can really help with making all these decisions. These questions are great to ask your customers, but they are also super helpful to ask yourself as you are developing a project. I find asking myself basic questions keeps things grounded in reality!

This applies best to projects early on in their development or refinement. You want to ask these questions before the engineering team has spent weeks doing calculations and making drawings or purchasing has got a ton of resin heading your way on a truck. These questions are decidedly less popular once teams (and bosses) have mentally committed to a course of action. Doesn’t mean you shouldn’t ask them – maybe just wear a helmet when you do.

If you have experience with a similar project or product, that can be a huge help. It is always easier to compare to something than to look at ideas just floating around unanchored. These questions are powerful in isolation, but can also be used to compare to a known part/process/project.

For specific considerations on manufacturing methods, see: Composite Manufacturing Methods.

Why Composites?

Whenever I see a different kind of project or request for a quote on something new or unusual, I have trained myself to think: Why is it being built from these materials? Could it be metal? How about solid plastic? Usually I already “know” why it’s being built as proposed but it really helps to consider why from a first-principles point of view. Many times I have been able to ask a few questions to clarify my understanding of this decision and I find that assumptions have been made that aren’t going to hold up gracefully in the face of reality. Of course I make assumptions too and so I find it really helpful to run my ideas by somebody else and get them to ask the “you’re not gonna hurt my feelings” questions.

Your job as a builder/manufacturer is to make valuable things happen for your customer – or boss, or whoever ultimately decides if you’re doing a good job. You need to know that the path you’re on is going to make that happen. There is nothing valuable about making something harder, more expensive, or out of tolerance. It is almost always better to send somebody down a path that is going to get them good results even if it doesn’t involve you making a sale. I only have these opinions because I have done what I was told lots of times even when it seemed like a bad idea – and lots of times it was. It is often good to push on assumptions a little to make sure things end up happier in the long run.

If the reason for composites is truly compelling and you can’t talk everybody out of it then you know you’re in a good place to start asking more specific questions!

How many do you need?

This is simple – but there are complications. For a manufactured product with predictable volumes and rates, it is relatively easy to settle on a manufacturing method that balances performance requirements and price. Actually getting it to go to plan is harder!

If you’re only making one then you have just the burden of considering how well to make it and what the demands are regarding performance, weight, tolerances, etc. The “how much would you like to pay” question below is really helpful here because it is pretty easy to predict costs for one-off things – and being wrong only hurts once!

Tooling costs are often vastly greater than actual part costs, especially for higher volume manufacturing processes. There’s a lot of risk up front and prototyping or dedicated development time and money is almost always needed. If you are a manufacturer, customers may tell you a bigger story than is actually there to get you to agree to “volume” pricing and to push more of the cost of development on you. They may not even be doing it intentionally – when you believe in something and you have those “rose colored glasses” on it’s easy to convey more confidence than an impartial observer would have. I have wasted a great deal of time and money developing projects where the market wasn’t actually there. Either price could not be made low enough without larger volume or lost performance – or there was nowhere near the promised volume when it came time to selling the actual product. Not to say that you shouldn’t take risks – but it is important to really dig into details. Try to hunt for assumptions and make sure you’re ok with them!

When you’re looking at a product with no proven sales, there’s a tension between getting something in hand soon to test/sell and being prepared to make more. I’m a big fan of prototyping in as similar a method as possible to how you hope to manufacture. Sure you can 3D print things or cover foam with fiberglass and paint it up nicely, but you’re not learning anything about how you’ll actually make the thing for real. Better (in my opinion) to make cheap rough tooling (MDF, tooling board, hand built) but use the actual proposed manufacturing method. This is hard/expensive if your volumes justify RTM in metal tools or you need giant carbon molds – but even in these cases, the actual manufacturing process is so critical to your ability to produce the parts that is is almost as important to test as the parts themselves.

What price would you like to pay for this product?

Good luck with this one! I have almost never gotten a straight answer to this but it is incredibly helpful in certain situations. If you are working to a competitive bid, it can be hard to get anybody to talk price at all – they just want your number. Its still good to ask, couched in terms of better understanding your customer’s (or boss’s) needs. This is especially important for new products – where there may be a business model based on certain price-related expectations. There may also be drawings with expensive details and tolerances with lots of decimal places, but if the “Ideally it would cost this much” price is way-unrealistic, it is best to discuss this up front before anybody wastes too much time. Many of the details may be “wishful engineering” or just plain misunderstanding of what is normal or possible with composites.

Sometimes people will giggle uncomfortably and say “Uhh, zero?” when asked about price. This is reasonable to expect – it’s kind of a funny question. If you can’t get a reasonable idea of a realistic price range it may be best to send your customer away to think about it – or to offer up a few tiers of pricing based on different processes. Often price is the biggest driver of a project’s success – both for the manufacturer and the customer. There has to be a way to land in the “win-win” zone or it’s not going to work.

If you are manufacturing your own products, this is a critical question and every bit as important as any other “performance” metric. It is easy to have things cost more than planned, and hard to get them to cost less. Be critical of your own assumptions and question areas that are complicated or otherwise expensive to see if you can remove or soften roadblocks to economy.

Is the schedule realistic?

Schedule can sometimes (always) be a hurdle for composites manufacturing projects. It takes a long time to get something up and running and the cost of changes mid-production can be huge. And the designing, planning and engineering really needs to be done before the tooling and purchasing and manufacturing work can begin – well, mostly. Sometimes it isn’t obvious how long this takes. Project management is the worst, but it’s way better than no project management!

It is likely that customers (internal or external) will want product quickly. This is both because they want to use or sell it and because they have spent a bunch of money on development that they want to see returning value. Laying out a hypothetical schedule early in the process before any contracts or agreements happen is key. Make sure you fight for a realistic (plus Murphy!) schedule for your deliverables. Lay out all deadlines for decisions and information. Make delivery dates contingent on complete information by a certain day. Unless this is thoroughly discussed before anybody commits to anything too serious, you are asking for trouble!

It is a good idea to lay out realistic early production volumes and make sure that your production capacity matches the business requirements of your customer. It isn’t a bad idea to estimate deliveries out several months or years (depending on the item and scale of time involved) just to make sure that in theory everybody is on the same page. If things aren’t aligned you’ll have time to work on solutions before it becomes a commercial problem.

How much will you pay to save one kg/lb?

This is one of the most revealing questions you can ask about a project – especially when deciding on manufacturing methods. Usually this is a hard answer to actually get. Racing teams, aircraft builders and people launching things into space will have a really good idea about how bad they want to save weight. Most other customers will find the question uncomfortable and hard to answer. This is totally reasonable. It is difficult to make “marginal” decisions because our brains aren’t well equipped to do it. I once asked my wife how much she would pay per day to have a certain piece of furniture we were considering. “Is that a 50-cents-a-day sofa dear?” Well ok, what’s the present value of 50 cents a day for ten years? It didn’t go over as well as I’d hoped. Turns out decisions are pretty emotional and often more binary than we’d like to admit.

So the easiest case is when you get “I don’t care what it weights – I just want the gelcoat finish.” or “Just whatever optimizes the cost of materials – weight isn’t an issue here.” These are great because now you know any effort to save weight is only worth it in terms of material or labor saved. This frees you up to ask important questions about finish, tolerance and cost.

Usually people are into composites because of one or more of the three “superpowers” I sometimes bring up around EC!. The first superpower is the option to make “anisotropic” layups – with reinforcement material pointed only in the direction of given loads. Superpower two is core. Cored “sandwich panel” composites offer unparalleled stiffness for their weight. Superpower three is the ease of making tooled surfaces with complicated geometry and nice surface finishes – and doing it over and over without out extra work. The first two of these play into the weight question in a serious way. Try to be sure you understand how important different parameters are to the “success” of the project. The more you understand the “why” – the better you can make sure the “how” matches up well. Of course there are other superpowers that are highly application specific and one of these may be in play!

Performance-Related Questions

After getting the hard questions out of the way, it becomes much easier to discuss the balance of price and performance. That “performance” may be weight, strength, stiffness, shininess, accuracy, thermal stability, corrosion resistance, etc. – or whatever mix of these is important. Because the groundwork has been set, these questions are much easier to negotiate without going down dead-ends and proposing things that have no potential to satisfy the real requirements.

Having considered these questions – and more of your own – it’s time to think specifically about what to do. What process makes sense? What materials should you use? What will the cycle time be? Can this resin handle the temperature? …and hundreds of other potential questions.

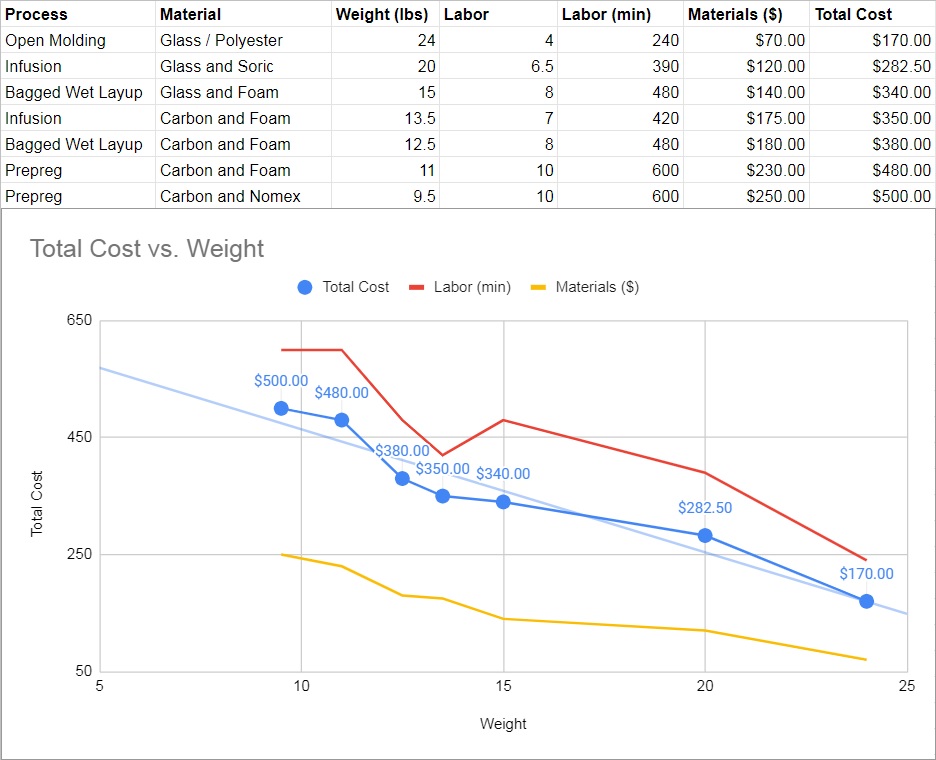

Long ago I studied economics. This was unwise probably, but it gave me a good appreciation of visualizing relationships between variables. Economists love them a graph! So imagine the curves showing the range of “crappy” to “awesome” vs. price for any performance metric. There isn’t a smooth gradient that can be landed on in any given spot – they’re stepped in not-obvious ways. Worse still – the “shapes” of the performance/cost curves impact each-other. You end up with a large multi-dimensional system of confusing factors – each one changing the others. It is reasonable to explain this to customers, bosses and other people involved in making decisions. Draw pictures if you can. Best case, try a spreadsheet with real estimates:

Here is a totally fictitious part of modest size and some (crude) estimates for cost and weight for a variety of materials and process types. This is a great way to visualize the costs (here: labor and material estimates) and the benefits (weight) for people involved in the decision process. You can see the high value relative to a trend-line of the infused and wet-laid carbon/foam options. If you have a real weight and price budget for the whole project you can play with different components and the choices to get the most weight saving for a given price.

Now imagine another requirement like “fire retardant resin” or RF-transparency” or just “durable gloss gelcoat finish” applied across this cost/weight graph. Any one of these would make any of the material/process combinations more or less viable. This kind of analysis in depth helps keep blind spots from cropping up and makes decisions easier and more readily defensible if goals seem to change in the future. And compared to any other part of the project, a few hours spent in spreadsheet-and-whiteboard-land will be some of the best hours you can spend.

Conclusions

If this all seems like common sense – that is good! My goal here is to suggest a thorough and systemic understanding of what is valued and what isn’t with regards to any given project or individual component. When in doubt – or if decisions are made by larger groups – it is good to estimate and visualize the numbers involved. Pictures are much easier to process than raw numbers – even if you are the one who generated the raw numbers. If your team has trouble answering the questions in this article, it may be time to pause and revisit the goals of the project and come up with a more rigorous understanding of what you need. This is the time to ask these kinds of questions!